- Home

- James Thurber

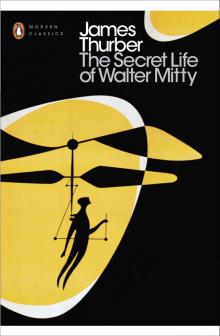

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty Read online

James Thurber

* * *

THE SECRET LIFE OF WALTER MITTY

Contents

The Lady on 142

The Catbird Seat

The Secret Life of James Thurber

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty

The Macbeth Murder Mystery

A Ride with Olympy

The Breaking Up of the Winships

A Couple of Hamburgers

Doc Marlowe

Snapshot of a Dog

Something to Say

The Kerb in the Sky

The Remarkable Case of Mr Bruhl

The Luck of Jad Peters

The Greatest Man in the World

The Evening’s at Seven

One is a Wanderer

The Night the Bed Fell

The Dog That Bit People

Follow Penguin

PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

THE SECRET LIFE OF WALTER MITTY

James Thurber was born in 1894 in Columbus, Ohio. After attending Ohio State University, he worked at the American Embassy in Paris from 1918 to 1920, and then turned his hand to journalism. He started working as a staff writer for the New Yorker in 1927, and the magazine subsequently published many of his inimitable articles and cartoons. As a child, Thurber had been blinded in one eye while playing a game of William Tell with his brothers; in later life he went completely blind, but nevertheless continued to write and draw. He died in New York in 1961.

Thurber’s art was easy to recognize but hard to define. He created a world in which mournfully sagacious hounds loom over frightened little men who are trying desperately to master life’s problems. His drawings and prose alike were marked by economy, wry humour and his own blend of precision and fantasy. These qualities are all abundantly apparent in the story of his most famous character, Walter Mitty – the shy dreamer whose secret life gloriously makes up for his failures in real life.

The Lady on 142

The train was twenty minutes late, we found out when we bought our tickets, so we sat down on a bench in the little waiting room of the Cornwall Bridge station. It was too hot outside in the sun. This midsummer Saturday had got off to a sulky start, and now, at three in the afternoon, it sat, sticky and restive, in our laps.

There were several others besides Sylvia and myself waiting for the train to get in from Pittsfield: a coloured woman who fanned herself with a Daily News, a young lady in her twenties reading a book, a slender, tanned man sucking dreamily on the stem of an unlighted pipe. In the centre of the room, leaning against a high iron radiator, a small girl stared at each of us in turn, her mouth open, as if she had never seen people before. The place had the familiar, pleasant smell of railroad stations in the country, of something compounded of wood and leather and smoke. In the cramped space behind the ticket window, a telegraph instrument clicked intermittently, and once or twice a phone rang and the stationmaster answered it briefly. I couldn’t hear what he said.

I was glad, on such a day, that we were going only as far as Gaylordsville, the third stop down the line, twenty-two minutes away. The stationmaster had told us that our tickets were the first tickets to Gaylordsville he had ever sold. I was idly pondering this small distinction when a train whistle blew in the distance. We all got to our feet, but the stationmaster came out of his cubby-hole and told us it was not our train but the 12.45 from New York, northbound. Presently the train thundered in like a hurricane and sighed ponderously to a stop. The stationmaster went out on to the platform and came back after a minute or two. The train got heavily under way again, for Canaan.

I was opening a pack of cigarettes when I heard the stationmaster talking on the phone again. This time his words came out clearly. He kept repeating one sentence. He was saying, ‘Conductor Reagan on 142 has the lady the office was asking about.’ The person on the other end of the line did not appear to get the meaning of the sentence. The stationmaster repeated it and hung up. For some reason, I figured that he did not understand it either.

Sylvia’s eyes had the lost, reflective look they wear when she is trying to remember in what box she packed the Christmas-tree ornaments. The expressions on the faces of the coloured woman, the young lady, and the man with the pipe had not changed. The little staring girl had gone away.

Our train was not due for another five minutes, and I sat back and began trying to reconstruct the lady on 142, the lady Conductor Reagan had, the lady the office was asking about. I moved nearer to Sylvia and whispered, ‘See if the trains are numbered in your timetable.’ She got the timetable out of her handbag and looked at it. ‘One forty-two,’ she said, ‘is the 12.45 from New York.’ This was the train that had gone by a few minutes before. ‘The woman was taken sick,’ said Sylvia. ‘They are probably arranging to have a doctor or her family meet her.’

The coloured woman looked around at her briefly. The young woman, who had been chewing gum, stopped chewing. The man with the pipe seemed oblivious. I lighted a cigarette and sat thinking. ‘The woman on 142,’ I said to Sylvia, finally, ‘might be almost anything, but she definitely is not sick.’ The only person who did not stare at me was the man with the pipe. Sylvia gave me her temperature-taking look, a cross between anxiety and vexation. Just then our train whistled and we all stood up. I picked up our two bags and Sylvia took the sack of string beans we had picked for the Connells.

When the train came clanking in, I said in Sylvia’s ear, ‘He’ll sit near us. You watch.’ ‘Who? Who will?’ she said. ‘The stranger,’ I told her, ‘the man with the pipe.’

Sylvia laughed. ‘He’s not a stranger,’ she said. ‘He works for the Breeds.’ I was certain that he didn’t. Women like to place people; every stranger reminds them of somebody.

The man with the pipe was sitting three seats in front of us, across the aisle, when we got settled. I indicated him with a nod of my head. Sylvia took a book out of the top of her overnight bag and opened it. ‘What’s the matter with you?’ she demanded. I looked around before replying. A sleepy man and woman sat across from us. Two middle-aged women in the seat in front of us were discussing the severe griping pain one of them had experienced as the result of an inflamed diverticulum. A slim, dark-eyed young woman sat in the seat behind us. She was alone.

‘The trouble with women,’ I began, ‘is that they explain everything by illness. I have a theory that we would be celebrating the twelfth of May or even the sixteenth of April as Independence Day if Mrs Jefferson hadn’t got the idea her husband had a fever and put him to bed.’

Sylvia found her place in the book. ‘We’ve been all through that before,’ she said. ‘Why couldn’t the woman on 142 be sick?’

That was easy. I told her. ‘Conductor Reagan,’ I said, ‘got off the train at Cornwall Bridge and spoke to the stationmaster. “I’ve got the woman the office was asking about,” he said.’

Sylvia cut in. ‘He said “lady”.’

I gave the little laugh that annoys her. ‘All conductors say “lady”,’ I explained. ‘Now, if a woman had got sick on the train, Reagan would have said, “A woman got sick on my train. Tell the office.” What must have happened is that Reagan found, somewhere between Kent and Cornwall Bridge, a woman the office had been looking for.’

Sylvia didn’t close her book, but she looked up. ‘Maybe she got sick before she got on the train, and the office was worried,’ said Sylvia. She was not giving the problem close attention.

‘If the office knew she got on the train,’ I said patiently, ‘they wouldn’t have asked Reagan to let them know if he found her. They would have told him about her when she got on.’ Sylvia resumed her reading.

‘Let’s stay out of it,’ she said. ‘It isn’

t any of our business.’

I hunted for my Chiclets but couldn’t find them. ‘It might be everybody’s business,’ I said, ‘every patriot’s.’

‘I know, I know,’ said Sylvia. ‘You think she’s a spy. Well, I still think she’s sick.’

I ignored that. ‘Every conductor on the line has been asked to look out for her,’ I said. ‘Reagan found her. She won’t be met by her family. She’ll be met by the F.B.I.’

‘Or the O.P.A.,’ said Sylvia. ‘Alfred Hitchcock things don’t happen on the New York, New Haven & Hartford.’

I saw the conductor coming from the other end of the coach ‘I’m going to tell the conductor,’ I said, ‘that Reagan on 142 has got the woman.’

‘No, you’re not,’ said Sylvia. ‘You’re not going to get us mixed up in this. He probably knows anyway.’

The conductor, short, stocky, silvery-haired and silent, took up our tickets. He looked like a kindly Ickes. Sylvia, who had stiffened, relaxed when I let him go by without a word about the woman on 142. ‘He looks exactly as if he knew where the Maltese Falcon is hidden, doesn’t he?’ said Sylvia, with the laugh that annoys me.

‘Nevertheless,’ I pointed out, ‘you said a little while ago that he probably knows about the woman on 142. If she’s just sick, why should they tell the conductor on this train? I’ll rest more easily when I know that they’ve actually got her.’

Sylvia kept on reading as if she hadn’t heard me. I leaned my head against the back of the seat and closed my eyes.

The train was slowing down noisily and a brakeman was yelling ‘Kent! Kent!’ when I felt a small cold pressure against my shoulder. ‘Oh,’ the voice of the woman in the seat behind me said, ‘I’ve dropped my copy of Coronet under your seat.’ She leaned closer and her voice became low and hard. ‘Get off here, Mister,’ she said.

‘We’re going to Gaylordsville,’ I said.

‘You and your wife are getting off here, Mister,’ she said.

I reached for the suit cases on the rack. ‘What do you want, for heaven’s sake?’ asked Sylvia.

‘We’re getting off here,’ I told her.

‘Are you really crazy?’ she demanded. ‘This is only Kent.’

‘Come on, sister,’ said the woman’s voice. ‘You take the overnight bag and the beans. You take the big bag, Mister.’

Sylvia was furious. ‘I knew you’d get us into this,’ she said to me, ‘shouting about spies at the top of your voice.’

That made me angry. ‘You’re the one that mentioned spies,’ I told her. ‘I didn’t.’

‘You kept talking about it and talking about it,’ said Sylvia.

‘Come on, get off, the two of you,’ said the cold, hard voice.

We got off. As I helped Sylvia down the steps, I said, ‘We know too much.’

‘Oh, shut up,’ she said.

We didn’t have far to go. A big black limousine waited a few steps away. Behind the wheel sat a heavy-set foreigner with cruel lips and small eyes. He scowled when he saw us. ‘The boss don’t want nobody up deh,’ he said.

‘It’s all right, Karl,’ said the woman. ‘Get in,’ she told us. We climbed into the back seat. She sat between us, with the gun in her hand. It was a handsome, jewelled derringer.

‘Alice will be waiting for us at Gaylordsville,’ said Sylvia, ‘in all this heat.’

The house was a long, low, rambling building, reached at the end of a poplar-lined drive. ‘Never mind the bags,’ said the woman. Sylvia took the string beans and her book and we got out. Two huge mastiffs came bounding off the terrace, snarling. ‘Down, Mata!’ said the woman. ‘Down, Pedro!’ They slunk away, still snarling.

Sylvia and I sat side by side on a sofa in a large, handsomely appointed living-room. Across from us, in a chair, lounged a tall man with heavily lidded black eyes and long, sensitive fingers. Against the door through which we had entered the room leaned a thin, undersized young man, with his hands in the pockets of his coat and a cigarette hanging from his lower lip. He had a drawn, sallow face and his small, half-closed eyes stared at us incuriously. In a corner of the room, a squat, swarthy man twiddled with the dials of a radio. The woman paced up and down, smoking a cigarette in a long holder.

‘Well, Gail,’ said the lounging man in a soft voice, ‘to what do we owe thees unexpected visit?’

Gail kept pacing. ‘They got Sandra,’ she said finally.

The lounging man did not change expression. ‘Who got Sandra, Gail?’ he asked softly.

‘Reagan, on 142,’ said Gail.

The squat, swarthy man jumped to his feet. ‘All da time Egypt say keel dees Reagan!’ he shouted. ‘All da time Egypt say bomp off dees Reagan!’

The lounging man did not look at him. ‘Sit down, Egypt,’ he said quietly. The swarthy man sat down. Gail went on talking.

‘The punk here shot off his mouth,’ she said. ‘He was wise.’ I looked at the man leaning against the door.

‘She means you,’ said Sylvia, and laughed.

‘The dame was dumb,’ Gail went on. ‘She thought the lady on the train was sick.’

I laughed. ‘She means you,’ I said to Sylvia.

‘The punk was blowing his top all over the train,’ said Gail. ‘I had to bring ’em along.’

Sylvia, who had the beans on her lap, began breaking and stringing them. ‘Well, my dear lady,’ said the lounging man, ‘a mos’ homely leetle tawtch.’

‘Wozza totch?’ demanded Egypt.

‘Touch,’ I told him.

Gail sat down in a chair. ‘Who’s going to rub ’em out?’ she asked.

‘Freddy,’ said the lounging man. Egypt was on his feet again.

‘Na! Na!’ he shouted. ‘Na de ponk! Da ponk bomp off da las’ seex, seven peop’!’

The lounging man looked at him. Egypt paled and sat down.

‘I thought you were the punk,’ said Sylvia. I looked at her coldly.

‘I know where I have seen you before,’ I said to the lounging man. ‘It was at Zagreb, in 1927. Tilden took you in straight sets, six-love, six-love, six-love.’

The man’s eyes glittered. ‘I theenk I bomp off thees man myself,’ he said.

Freddy walked over and handed the lounging man an automatic. At this moment, the door Freddy had been leaning against burst open and in rushed the man with the pipe, shouting, ‘Gail! Gail! Gail!’ …

‘Gaylordsville! Gaylordsville!’ bawled the brakeman. Sylvia was shaking me by the arm. ‘Quit moaning,’ she said. ‘Everybody is looking at you.’ I rubbed my forehead with a handkerchief. ‘Hurry up!’ said Sylvia. ‘They don’t stop here long.’ I pulled the bags down and we got off.

‘Have you got the beans?’ I asked Sylvia.

Alice Connell was waiting for us. On the way to their home in the car, Sylvia began to tell Alice about the woman on 142. I didn’t say anything.

‘He thought she was a spy,’ said Sylvia.

They both laughed. ‘She probably got sick on the train,’ said Alice. ‘They were probably arranging for a doctor to meet her at the station.’

‘That’s just what I told him,’ said Sylvia.

I lighted a cigarette. ‘The lady on 142,’ I said firmly, ‘was definitely not sick.’

‘Oh, Lord,’ said Sylvia, ‘here we go again.’

The Catbird Seat

Mr Martin bought the pack of Camels on Monday night in the most crowded cigar store on Broadway. It was theatre time and seven or eight men were buying cigarettes. The clerk didn’t even glance at Mr Martin, who put the pack in his overcoat pocket and went out. If any of the staff at F. & S. had seen him buy the cigarettes, they would have been astonished, for it was generally known that Mr Martin did not smoke, and never had. No one saw him.

It was just a week to the day since Mr Martin had decided to rub out Mrs Ulgine Barrows. The term ‘rub out’ pleased him because it suggested nothing more than the correction of an error – in this case an error of Mr Fitweiler. Mr Martin had spent each night of the past

week working out his plan and examining it. As he walked home now he went over it again. For the hundredth time he resented the element of imprecision, the margin of guesswork that entered into the business. The project as he had worked it out was casual and bold, the risks were considerable. Something might go wrong anywhere along the line. And therein lay the cunning of his scheme. No one would ever see in it the cautious, painstaking hand of Erwin Martin, head of the filing department at F. & S., of whom Mr Fitweiler had once said, ‘Man is fallible but Martin isn’t.’ No one would see his hand, that is, unless it were caught in the act.

Sitting in his apartment, drinking a glass of milk, Mr Martin reviewed his case against Mrs Ulgine Barrows, as he had every night for seven nights. He began at the beginning. Her quacking voice and braying laugh had first profaned the halls of F. & S. on 7 March 1941 (Mr Martin had a head for dates). Old Roberts, the personnel chief, had introduced her as the newly appointed special adviser to the president of the firm, Mr Fitweiler. The woman had appalled Mr Martin instantly, but he hadn’t shown it. He had given her his dry hand, a look of studious concentration, and a faint smile. ‘Well,’ she had said, looking at the papers on his desk, ‘are you lifting the oxcart out of the ditch?’ As Mr Martin recalled that moment, over his milk, he squirmed slightly. He must keep his mind on her crimes as a special adviser, not on her peccadillos as a personality. This he found difficult to do, in spite of entering an objection and sustaining it. The faults of the woman as a woman kept chattering on in his mind like an unruly witness. She had, for almost two years now, baited him. In the halls, in the elevator, even in his own office, into which she romped now and then like a circus horse, she was constantly shouting these silly questions at him. ‘Are you lifting the oxcart out of the ditch? Are you tearing up the pea patch? Are you hollering down the rain barrel? Are you scraping around the bottom of the pickle barrel? Are you sitting in the catbird seat?’

It was Joey Hart, one of Mr Martin’s two assistants, who had explained what the gibberish meant. ‘She must be a Dodger fan,’ he had said. ‘Red Barber announces the Dodger games over the radio and he uses those expressions – picked ’em up down South.’ Joey had gone on to explain one or two. ‘Tearing up the pea patch’ meant going on a rampage; ‘sitting in the catbird seat’ meant sitting pretty, like a batter with three balls and no strikes on him. Mr Martin dismissed all this with an effort. It had been annoying, it had driven him near to distraction, but he was too solid a man to be moved to murder by anything so childish. It was fortunate, he reflected as he passed on to the important charges against Mrs Barrows, that he had stood up under it so well. He had maintained always an outward appearance of polite tolerance. ‘Why, I even believe you like the woman,’ Miss Paird, his other assistant, had once said to him. He had simply smiled.

The 13 Clocks

The 13 Clocks The Wonderful O

The Wonderful O The Secret Life of Walter Mitty

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty Writings and Drawings

Writings and Drawings The Thurber Carnival

The Thurber Carnival Collected Fables

Collected Fables Thurber: Writings & Drawings

Thurber: Writings & Drawings